What’s the right way to mark Juneteenth? The newest US holiday is confusing Americans

The United States’ newest federal holiday, celebrated annually on June 19, has quickly become its most puzzling one. Four years after President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act, Americans have wrestled with what to make of the holiday.

What is Juneteenth? What is the proper way to celebrate it? Should holiday observers attend barbecues and cookouts? Should Juneteenth’s observance be a day of learning? Is there a way to acknowledge the holiday without misappropriating it?

This confusion likely emerged because many Americans did not even learn about Juneteenth until around when it became a federal holiday in 2021. Moreover, the Trump administration and state legislatures across the country have further complicated matters with their increased efforts to ban the type of education that led to the national recognition of the holiday in the first place.

‘All slaves are free’

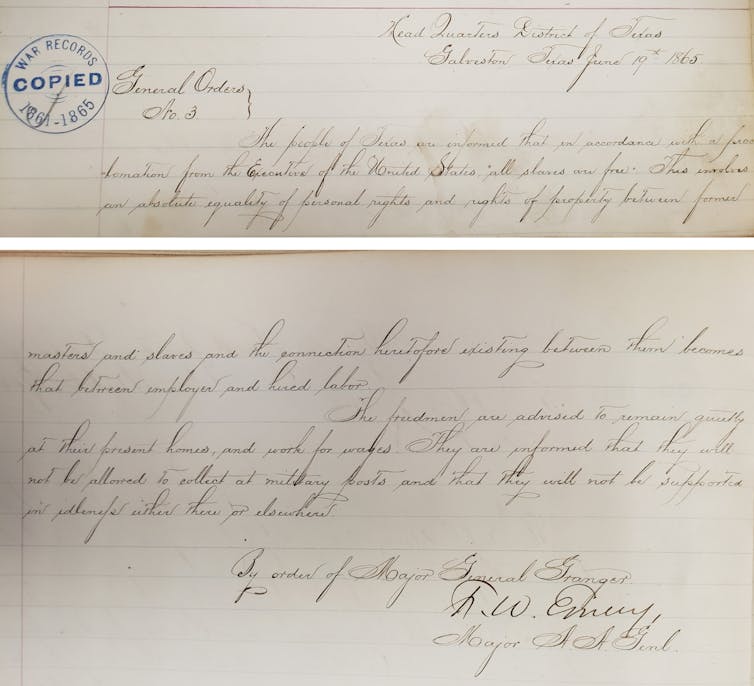

Juneteenth – short for June Nineteenth – recognizes the day in 1865 when Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, with roughly 2,000 federal troops from the 13th Army Corps. Upon arriving, Granger issued General Order No. 3. The order read:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Granger’s order effectively freed 250,000 enslaved people in the region.

Though President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the enslaved in all the states that had seceded from the U.S., nearly 2½ years earlier, Texas, a Confederate state, rebelled against it.

At the time, Texas had a minimal number of Union soldiers to enforce the proclamation’s emancipation of enslaved people residing within Confederate territory. Consequently, many of those enslaved in Texas remained ignorant of the proclamation’s potential impact on their lives, or of the fact the Civil War had functionally ended two months earlier.

In an interview published in 1941, for example, Laura Smalley of Hempstead, Texas, remembered how her enslaver fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. He returned without informing those whom he enslaved of their freedom. In her interview, she recounted, “Old master didn’t tell, you know, they was free … I think now they say they worked them, six months after that.”

‘Second Independence Day’

June 19, 1865, a Monday, changed that.

The news of emancipation culminated a generations-long struggle for Black people to obtain a modicum of freedom in the U.S.

For this reason, some refer to Juneteenth as the nation’s second Independence Day. The end of bondage was ostensibly codified in the 13th Amendment ratified later that year.

Spontaneous Juneteenth celebrations emerged almost immediately. Celebrants referred to the day as “Emancipation Day,” “Freedom Day,” “Juneteenth” and “Jubilee Day.” The latter title alluded to the biblical period following seven sabbatical cycles that resulted in canceling debts and freeing the enslaved.

Flake’s Bulletin, a weekly, Galveston-based publication, reported on an Emancipation Celebration occurring on Jan. 2, 1866, that included upward of 800 people. A similar gathering occurred in Galveston on June 19, 1866, in what is now the church known as Reedy Chapel AME. Annual celebrations continued, beginning in southeastern Texas, with events such as historical reenactments, parades, picnics, music and speeches.

Legacies of slavery

While the holiday marked a joyous occasion for some, Juneteenth met early and persistent opposition, particularly in the time following Reconstruction.

For years, local reporting spoke of Juneteenth, as the Galveston Historical Foundation put it, in a “flagrantly racist nature.” Additionally, the racist stereotyping – “idleness” – in the final sentence of Granger’s order simultaneously illustrated its complicated nature while also “[foreshadowing] that the fight for freedom would continue,” National Archives staffer Michael Davis wrote in 2020.

Historian Keisha Blain explains, “The enslavement of Black people in the U.S. may have ended but the legacies of slavery still shape every aspect of Black life.”

Advocates such as Opal Lee, commonly referred to as the “grandmother of Juneteenth,” pressed for Juneteenth celebration to continue and, ultimately, for it to be made a national holiday.

Lee began her advocacy in earnest during the mid-1970s in the Fort Worth, Texas, area. The oldest member of the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation, Lee spearheaded several campaigns to draw attention to Juneteenth. These campaigns included initiatives such as an online petition promoting the holiday’s observance launched in 2019 that amassed 1.6 million signatures.

In speaking on the significance of Juneteenth, Lee said, “Freedom is for everyone. I think freedom should be celebrated from the 19th of June to the Fourth of July; however, none of us are free until we are all free. We are not free yet, and Juneteenth is a symbol of that.”

National recognition

Because of this advocacy, Juneteenth has grown from relatively obscure regional celebrations to, starting in 2021, a federal holiday.

The establishment of the holiday was the capstone of initiatives during the racial reckoning. Historians refer to the racial reckoning as the time period beginning in the summer of 2020 until the spring of the following year that witnessed heightened attention to America’s nagging history of racism.

This reckoning included the historic protests prompted by the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery.

During this time, numerous institutions, ranging from colleges and universities to major companies, made commitments to racial equity. The recognition of Juneteenth represented a symbolic means to honor those commitments.

In remarks marking his signing of the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act, Biden said, “Juneteenth marks both the long, hard night of slavery and subjugation, and a promise of a brighter morning to come.”

Backtracking on gains

But within a year, some had already begun to argue the nation had, as community organizer Braxton Brewington wrote, “betrayed the spirit of Jubilee Day.”

Many of the racial equity commitments made during the racial reckoning quickly vanished within a year or two. Economist William Michael Cunningham revealed American companies pledged $50 billion to racial equity efforts in 2020, yet had only spent $250 million by 2021.

By the spring of 2025, companies such as Walmart and McDonald’s announced they will discontinue their diversity, equity and inclusion work. Moreover, Walmart will stop using the term altogether. Amazon, Meta and dozens of other large corporations made similar announcements.

And members of the Trump administration have mounted continual attacks on diversity, equity and inclusion policies and used the term as a politically expedient slur to deride Black people. This is also exacerbated by the Trump administration’s challenges to birthright citizenship, a key right that gave citizenship to the formerly enslaved and later guaranteed important rights to the entire populace.

This major shift has fueled arguments that the U.S. has regressed from efforts toward racial equity and thus undermined the meaning of Juneteenth. And such backtracking arguably makes some Juneteenth celebrations performative exercises rather than celebrations of true racial equity.

As one critic asked, has the holiday devolved “into an exploitative and profit-driven enterprise for companies that disregard the true significance of this day to the Black community?”

All of this has led to increasing confusion over how to commemorate Juneteenth, if at all. Juneteenth is not the first federal holiday with a complicated history. Nevertheless, with other complex holidays, Americans had years to process their misgivings. In short, the nation is still deciding what it means to be free.

Informacion mbi burimin dhe përkthimin

Ky artikull është përkthyer automatikisht në shqip duke përdorur teknologjinë e avancuar të inteligjencës artificiale.

Burimi origjinal: theconversation.com